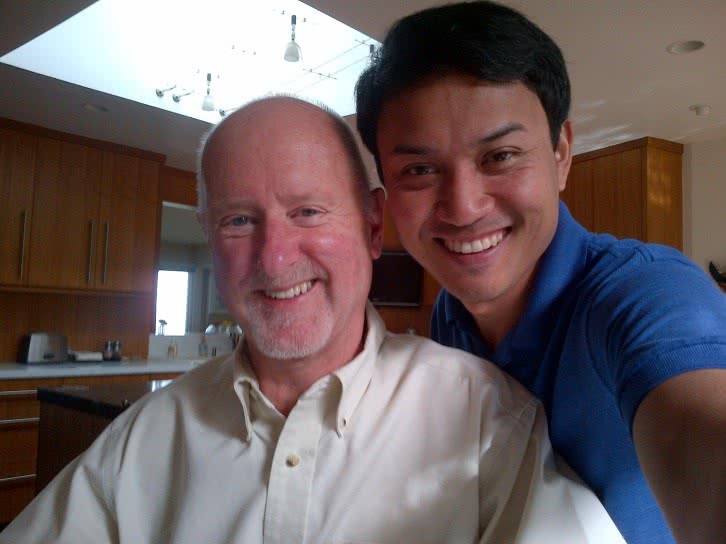

In December 2021, CLA Executive Director Phloeun PRIM sat down with CLA supporter Dana White for a recorded conversation during a recent trip to the US. Dana reflected on his longtime involvement with CLA and why his experience in Cambodia—spanning five trips that date as far back as 2004—has been so meaningful. Below are excerpts from their interview, lightly edited for clarity:

Phloeun: Hello Dana, thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview.

Dana: My pleasure, Phloeun.

Phloeun: My first question is: What brought you to Cambodia and Cambodian Living Arts?

Dana: Well, thinking back…my brother served on the board of CLA for many years before I was involved, and he invited me to join him in Cambodia in 2004 to see what it was all about. That was my first time in Cambodia, and certainly the first time I had been involved with CLA.

Cambodia fascinated me. At first it was very difficult for me traveling there. I’m a spoiled Californian. At first I had a hard time but then I visited some arts classes [organized by CLA] and suddenly it became more accessible to me, seeing young people learning how to dance, learning how to sing, how to play instruments. Since my whole career was as a teacher, I felt very comfortable with the young people I met. I became more interested in what Cambodian Living Arts was trying to accomplish.

I had read about Pol Pot and the horrors of what happened in Cambodia. I had a sense of guilt about what America had done in Cambodia with the bombings, and the confusion, the craziness of Vietnam in Cambodia. All of this sort of tied together: a fascination with the young people, what CLA was teaching them, and the need to resurrect Cambodia, especially after what America had done there.

Phloeun: It’s been more than a decade—maybe between 15-20 years since your first trip to Cambodia. What has kept you engaged and returning to Cambodia five times?

Dana: Why did I keep going back? I remained very interested in the mission of Cambodian Living Arts and the country’s revival. I really loved Arn’s expression, “Cambodia will be a country known for its arts, not for the genocide,” and there was a continuing sense that America owed Cambodia something, that I owed Cambodia something after what we did in Cambodia. I despised Nixon, so in a way I was thumbing my nose at Nixon: “Look, you can bomb it, but we can rebuild it.”

Then I got involved with teaching there. I taught English to Cambodian young people. I don’t think I did much as a teacher, but I’d be surprised every now and then at something the students would remember. Once I used a speech by Martin Luther King Jr. to bring an idea of what America is. My students were overwhelmed by the size of America.

Phloeun: Two years ago, Cambodian Living Arts turned 20. It’s quite amazing for a small grassroots organization to keep going for 20 years. It’s almost like the beginning of adulthood. What I keep telling people is, ‘for us, for me, 20 years means a lot because it means that we’ve nurtured a generation so that these people now—when we started they were young, and some of them were teenagers—and now they either lead their own organizations, lead their own projects, or teach. So what I’m looking at now is the next 20 or 50 years for CLA, where we can continue to learn from the past 20 years of practices that we’ve done as a grassroots organization and growing as we are, and then keep being relevant. I like to use that term because it doesn’t mean we have to do exactly the same as we did 20 years ago or 15 years ago, because I think as the context of the country is changing, our relevancy is even more important.

Today I would say one of the most relevant issues that we’ve seen came from a review of our scholarship program. We asked the students, “which aspect of the program could be more beneficial for you?” And they said “tackling social issues within the country.” 20 years ago it was about reviving traditional performing arts that were about to disappear. We built a whole new generation of artists, and not just artists but teachers also. So I think although that restoration still needs to continue, because there are some art forms that still need attention, we really shifted toward giving the tools for that young generation to be able to express and create something that is relevant to Cambodia today. And bringing up social issues, environmental issues through arts and culture is something we are really trying to encourage. It’s not about—in the Western world, they would use the term “arts activism”—we’re not trying to create activists, but we are trying to get young people interested to be involved within their society to make a difference.

So if I asked you as a donor who has been supporting us for the last 10-15 years, is there a message you’d like to give us as we are looking to the next 20, 30, 40 years?

Dana: Some of what you just said surprises me, but I think addressing climate change is one of the most important issues in our world. How can Cambodian Living Arts help with the issue of climate change? It’s an enormous issue. Cambodia could just disappear if we don’t take care of climate change. Before the arts, tackling climate change is probably more important.

Phloeun: We’ve been doing a Cultural Season festival every year in Cambodia. The past three years have been around identity—understanding Cambodian identity, creating Cambodian identity, and engaging with the diversity identities within the country. We give these themes to artists to inspire them and help them create work around those themes. But this year, we decided to shift the theme completely, [from identity] to “Action Today, Consequences Tomorrow.” So we gave that prompt to the artists and asked “What are the actions that you are taking today, and what are the consequences for tomorrow?” So we didn’t say that the theme is specifically around sustainability and environmental issues, but that’s our inspiration.

For example, around the development of the city [of Phnom Penh]—lately [the government] has been pumping sand from the Mekong River to fill lakes within the city, and we think that will have environmental consequences for tomorrow. It could be around the Mekong River, the dams; it could be around cutting trees.

Dana: How does action today work with climate change?

Phloeun: That depends on the artists. If today we allow people to cut down trees, then tomorrow what will remain of our tropical forests? If we say that because we need energy, we need to build more dams, and we cut the flow of the Mekong River, where will the fish go?

We didn’t want to tell the artists exactly what they would work on, but we wanted to inspire them to think about that theme as they create a dance piece, or a theater play, or lyrical songs—it’s all toward that theme and that reflection.

Dana: That’s excellent. I remember once several students saying to me as I put up a map of the world, that “Cambodia is so small” and they’d look at the map and feel insignificant. “Who are we? We’re a tiny little country in the middle of these world powers. We don’t mean much.” But if they have the goal that you can’t cut down their forests, you can have an effect, and that’s true with any of the countries surrounding Cambodia.

Cambodia has been in such a terrible situation for so many decades, and what I love is that you’re now talking about the environmental threat of cutting down forests. When you go back to Pol Pot and the massacres, you’ve come a long way from that—a long, long way. One thing that really struck me driving around Cambodia were the glass enclosures with skulls in them. And you realize that’s what people were dealing with: the killing of civilians, of people—not soldiers; people. Cambodia may seem small and it is small on a larger scale, but it’s very big, certainly in Southeast Asia.

I don’t know if other countries have the same sort of program as Cambodian Living Arts, or can inspire young people to think, “OK, we shouldn’t keep cutting down the forest, we shouldn’t be damming up the river, and I can create a dance around that, or I can create certain paintings around that, I can use the arts to impress upon people the idea that we may be small, but we do have significance.” All of Southeast Asia is of huge importance to the world. If Cambodia can impress its neighbors, more power to them.

Phloeun: Is there anything else you’d like to share as a long term supporter and also friend of—not just the organization, but also so many people—as a friend of mine, and as you’ve come to know many of these young people who I’m sure, as you have the chance to go back to Cambodia, will all recognize you and say, “Dana!” Is there anything else you want to add?

Dana: I just look at the faces of all my friends in Cambodia and they flood me with memories, like one time I officiated a wedding—that was a very personal thing. CLA is not just an impersonal organization. It’s people. And that for me is the most important thing.

Since his first trip to Cambodia in 2004, Dana White has made several transformational gifts to Cambodian Living Arts, supporting the Arn Chorn-Pond Living Arts Scholarship, Bangsokol: A Requiem for Cambodia, general operating costs, and other special projects that have contributed to the growth and sustainability of CLA.